Standard dementia care often focuses on management of responsive behaviors and keeping a person safe. With the current structure of elder care, people living with dementia frequently become passive recipients of care and spend long periods of time sitting, which leads to boredom, anxiety, increased confusion, depression, a variety of negative behaviors, and poor quality of life. When a person with dementia experiences such a poor quality of life, it’s guaranteed that his or her family and staff of caregivers are also experiencing quite a bit of stress and strain.

Why?

Because a person living with dementia simply doesn’t (and can’t) think the way you or I do. Thus, by trying to control any behavior you don’t like, you only exacerbate it — causing both you and your loved one to feel frustrated, angry, confused and exhausted.

In short, when we treat people like a “problem” to be managed, it’s stressful for everyone.

People living with dementia, are just that, people. People who took care of themselves and their children, had jobs or responsibilities for contributing to society, and now are being taken care of by you. Just like you, they want to spend their days doing something worthwhile.

Think about it: for most of your adult life when you meet someone new, you often ask, “What do you do?”

Many of us identify ourselves by the work we do, whether that may be working as a professional outside of the home or as a homemaker or parent or care partner. Meaningful work gives our lives purpose.

The need to have purpose in one’s life and to be productive doesn’t end once someone receives a diagnosis of dementia.

So, if you’re frustrated and exhausted as a care partner of a person with dementia, first of all, please know that you are NOT alone.

Allow me to present a different approach to you.

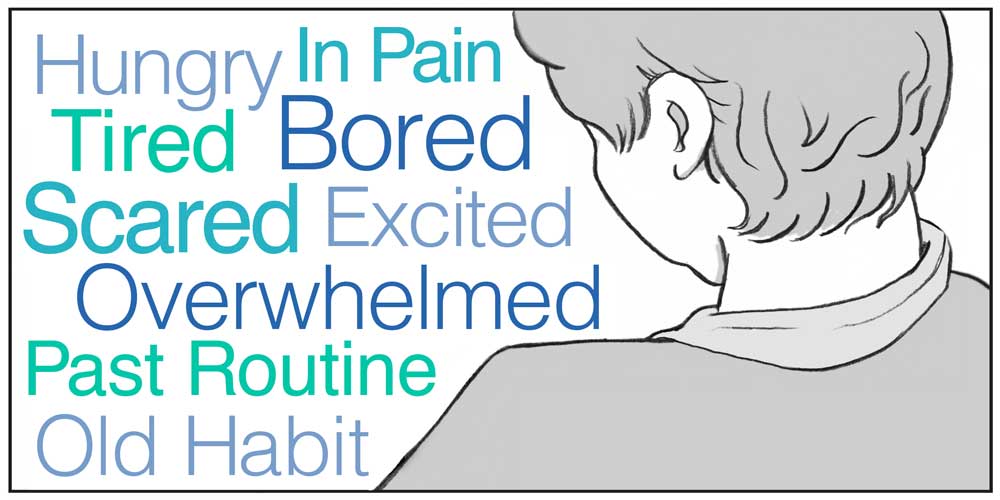

Very often people with dementia communicate with us by using actions, words and gestures that we may not understand right away, but are an expression of something important about their personal, social or physical environment.

These are referred to as responsive behaviors and usually occur because the person has a need that is not being met and does not know how or is unable to express this in words. Responsive behaviors can be frustrating and challenging for care partners and can occur suddenly at any stage of the dementia.

I like to prevent responsive behaviors from happening in the first place, by ensuring that people with dementia are not only safe, but active doing things in their life they enjoy, and that help to meet their needs and maintain their roles and identity throughout the full course of their life.

My philosophy of living focuses on engaging the older adult in an environment that is adapted to support memory loss and sensory impairment, and to facilitate independence. As a result, elders are empowered to care for themselves and others, make contributions to their community, and engage in meaningful activities. When elders are engaged doing things they love, staff burden, stress, and assistance time is decreased.

Meet Henry

Henry walked into the darkened kitchen, felt for the knob and opened the drawer to the left of the sink. He pushed the utensils from side to side, touching and removing each one, inspecting the spoons and spatulas, then shaking his head before placing each one back in a hurried, disorderly fashion.

Slam!

“Not in here,” he muttered as he moved to open the next drawer.

“What in God’s name are you doing in here so early?” yelled his wife, Evelyn, as she stomped back into the bedroom. “It’s not even five o’clock. Stop that and come back to bed!”

Unfortunately, this scene is all too common for homes in which someone is living with dementia.

Henry’s wife, Evelyn, is exhausted, and for good reason. She is tired of being awakened early in the morning by the slamming of drawers and weary from trying to convince her husband to go back to bed.

She is drained of energy by putting her household back into place each day after Henry rearranges everything.

Thinking she was being clever, Evelyn tried removing everything from the kitchen drawers except for the few most needed items, but that seemed to make Henry even more agitated.

What can she do to make this stop? She doesn’t want Henry to live in a nursing home, but truly she can’t live like this much longer.

Often when reacting to behaviors of someone with dementia, family members respond by removing the item that is being used inappropriately or by restricting movement because of safety concerns, but this is not always the best solution — and often, can intensify the problem.

Let’s consider Henry’s situation. In his younger years, he had an active career as a teacher, and he could also fix anything. He loved puttering in the garage, building window boxes and bird houses for the garden and growing vegetables.

It is very likely that Henry is looking for one of his tools or something to do each morning when he’s rummaging in the kitchen. What appears to be irrational and random is actually an effort at having meaning and purpose in his life.

If he has always liked fixing things, perhaps he wants to feel useful or helpful. We all like to have something meaningful to do.

Henry may not be able to use power tools, build a complicated bird house, or change the oil in the car anymore, but given the opportunity and, if needed, a bit of assistance, Henry could sand and paint an already constructed bird feeder, pick the vegetables, and wash the car.

A card table set up in the kitchen with items to repair, sand, paint or assemble would probably hold Henry’s attention and create a useful distraction from rummaging in the utensil drawers.

If Evelyn redirects Henry’s energies toward his natural abilities and offers him choices of things to do based on his past interest and habits, she will begin to establish balance and harmony in the home.

If there was an ongoing project on the kitchen table for Henry, he may work on that instead of disturbing the utensils.

When our loved ones act in strange ways, it is very easy, and understandable to become frustrated. However, our anger isn’t going to make the person feel better or act differently. In most cases, the person will respond to this negativity by becoming apathetic, frustrated, aggressive or defensive. Try to keep in mind that this person is living every day with a disease that is causing the brain to malfunction, to operate while it is broken. It is like trying to complete a puzzle when some of the pieces are missing. Instead of being angry, view the behaviors of someone with dementia as a form of communication.

Our Hand in Hand approach provides simple strategies on our site for everyone; we are sure you’ll find something that is the right fit for you. Browse through the topics below and find ones that interest you. There will certainly be many suggestions that jump right out at you because you are having some challenges. Read through the material and try some of the strategies that resonate with you. Make adjustments that fit your lifestyle and needs. But, make sure you try them! You’ll be amazed at how easily you can help your loved one go from stressed or confused to content or engaged. Use our Contact Us page to let us know what you tried and how it worked.

About Jennifer Brush

Educator, Ohio Council for Cognitive health

Jennifer Brush, MA, CCC/SLP is an award-winning Dementia Educator, author and consultant. Passionate about enriching the lives of people with dementia, Jennifer is on a mission to put the focus of care on the person’s preferences, interests and abilities. Jennifer flawlessly bridges the gap between care communities and the individuals they serve. Jennifer serves on the Association Montessori International (AMI) Advisory Board for Montessori for Aging and Dementia. She conducts research that has been funded by private foundations as well as the National Institutes of Health. Jennifer is the author of five nationally recognized books on dementia. Currently she is busy writing our educational material to support caregivers.